Some links may be affiliate links. We get money if you buy something or take an action after clicking one of these links on our site.

Christmas All The Time is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Historical Grinches – Revolutionary France

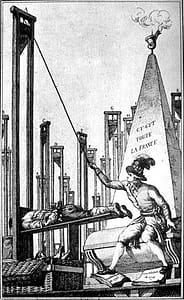

The last decade of the Eighteenth Century saw a massive upheaval in France.  The monarchy was abolished and the monarchs were decapitated. A republic was declared and extended periods of violent tumult shook the country. Along with the overthrow of the monarchy and the aristocracy, republican sentiment was turned against the clergy. The clergy had justified the right of the nobility to rule throughout medieval history. While redefining how government worked, some of the revolutionary leaders were also trying to redefine French culture according to Enlightenment ideals. In deposing the nobility and the clergy, Christianity (and therefore Christmas) was replaced by some pet theories.

The monarchy was abolished and the monarchs were decapitated. A republic was declared and extended periods of violent tumult shook the country. Along with the overthrow of the monarchy and the aristocracy, republican sentiment was turned against the clergy. The clergy had justified the right of the nobility to rule throughout medieval history. While redefining how government worked, some of the revolutionary leaders were also trying to redefine French culture according to Enlightenment ideals. In deposing the nobility and the clergy, Christianity (and therefore Christmas) was replaced by some pet theories.

French Republican Calendar

In an attempt to cast off all things of the past and move toward an Age of Reason, a decimal calendar was designed with decimal time. Twelve months of thirty days were given entirely new names: Vendémiaire (“grape harvest”), Brumaire (“mist”), Frimaire (“frost”), Nivôse (“snowy”), Pluviôse (“rainy”), Ventôse (“windy”), Germinal (“germination”), Floréal (“flower”), Prairial (“meadow”), Messidor (“harvest”), Thermidor or Fervidor (“summer heat”), Fructidor (“fruit”). Certainly, this caused some confusion abroad. One Brit provided an easier translation for his countrymen in Sporting Magazine’s January 1800 edition: Wheezy, Sneezy and Freezy; Slippy, Drippy and Nippy; Showery, Flowery and Bowery; Hoppy, Croppy and Poppy.

Each week had ten days. Each day had ten hours. Each hour had one hundred minutes. Each minute had 100 seconds. The remaining five days (or six in a leap year) were designated as “complementary days” which served as a collection of civic holidays. The calendar began on the Autumnal Equinox, so the Complementary Days which they called les sans-culottides fell in mid-September. The holidays were celebrations of certain concepts such as the “Celebration of Virtue (La Fête de la Vertu)” or the “Celebration of Labor (La Fête du Travail)”. For fairly obvious reasons, the calendar just never caught on and went out of use in 1805.

Cult of Reason

To define a new belief system is no minor feat. Using Enlightenment ideals and philosophical concepts from Rousseau and others, they defined a civic religion. They sought the perfection of mankind through Truth and Liberty, discounting any concept of a supernatural being. Rather than prayers to God, they would seek perfection through the exercise of Reason.

To define a new belief system is no minor feat. Using Enlightenment ideals and philosophical concepts from Rousseau and others, they defined a civic religion. They sought the perfection of mankind through Truth and Liberty, discounting any concept of a supernatural being. Rather than prayers to God, they would seek perfection through the exercise of Reason.

On 20 Brumaire Year II (10 November 1793), they celebrated the Fête de la Raison nationwide in decommissioned churches and cathedrals that were retasked as Temples of Reason. In concern of lapsing into idolatry, such Fêtes featured a live Goddess of Reason attended by young girls in white tunics and tricolor sashes. It was increasingly popular among the masses, but was repudiated by Maximilien Robespierre who had a religion of his own to roll out.

Cult of the Supreme Being

At the height of his Reign of Terror, Robespierre, finding the Fête de la Raison at Notre Dame in Paris to be a deplorable affair and finding the Cult of Reason to be too far gone on the road to dechristianization, had the leaders of that movement arrested and executed. This wasn’t terribly surprising. Robespierre had already had tens of thousands of people executed in France for being “enemies of the revolution”. Being rid of his competitors, Robespierre rolled out his new Revolutionary religion. He put forward that reason was only a means to an end. The end was a civic-minded public virtue of the type seen in Ancient Rome and the early Greek city-states. His reliance on a god figure to represent a higher moral code as “constant reminders of justice” that he believed to be essential to the Republic.

At the height of his Reign of Terror, Robespierre, finding the Fête de la Raison at Notre Dame in Paris to be a deplorable affair and finding the Cult of Reason to be too far gone on the road to dechristianization, had the leaders of that movement arrested and executed. This wasn’t terribly surprising. Robespierre had already had tens of thousands of people executed in France for being “enemies of the revolution”. Being rid of his competitors, Robespierre rolled out his new Revolutionary religion. He put forward that reason was only a means to an end. The end was a civic-minded public virtue of the type seen in Ancient Rome and the early Greek city-states. His reliance on a god figure to represent a higher moral code as “constant reminders of justice” that he believed to be essential to the Republic.

On 20 Prairial Year II (8 June 1794), Robespierre held the first Festival of the Supreme Being and decided that ongoing republican holidays would take place on the tenth day of each week. The festival was one of many excesses that led to the Thermidorian Reaction, which was a coup d’etat against Robespierre and the Jacobins in the revolutionary government. The Cult of the Supreme Being ended with Robespierre’s visit to the guillotine on July 28th 1794.

The French Revolution wasn’t the last overthrow of a monarchy that led to excesses in reshaping society at the cost of tens of thousands of lives. Stay tuned for our next historical grinches! Joyeux Noël!